Republic of China (1912–1949)

Republic of China | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1949 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Anthem: Various

| |||||||||||

National seal (1929–1949) | |||||||||||

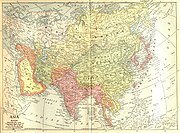

Land controlled by the Republic of China (late 1945) shown in dark green; land claimed (until early 1946) but not controlled shown in light green. | |||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| Largest city | Shanghai | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Standard Chinese | ||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | See Religion in China | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Chinese[1] | ||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1912 (first, provisional) | Sun Yat-sen | ||||||||||

• 1948–1949 | Chiang Kai-shek | ||||||||||

• 1949–1950 (last) | Yan Xishan (acting) | ||||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||||

• 1912–1916 (first) | Li Yuanhong | ||||||||||

• 1948–1954 (last) | Li Zongren | ||||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||||

• 1912 (first) | Tang Shaoyi | ||||||||||

• 1949 (last) | He Yingqin | ||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||

| Control Yuan | |||||||||||

| Legislative Yuan | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 10 October 1911 – 12 February 1912 | |||||||||||

| 1 January 1912 | |||||||||||

• Admission to the League of Nations | 10 January 1920 | ||||||||||

| 1926–1928 | |||||||||||

| 24 October 1945 | |||||||||||

| 25 December 1947 | |||||||||||

| 7 December 1949[a] | |||||||||||

| 1 May 1950 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1912 | 11,364,389 km2 (4,387,815 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 1946 | 9,665,354 km2 (3,731,814 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1949 | 541,000,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 to +8:30 (Kunlun to Changbai Standard Times) | ||||||||||

| Drives on | Left until 1946, right afterward | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| History of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

The Republic of China (ROC) began on 1 January 1912 as a sovereign state in mainland China[b] following the 1911 Revolution, which overthrew the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and ended China's imperial history. From 1927, the Kuomintang (KMT) reunified the country and ruled it as a one-party state with Nanjing as the national capital. In 1949, the KMT-led government was defeated in the Chinese Civil War and lost control of the mainland to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The CCP established the People's Republic of China (PRC) while the ROC was forced to retreat to Taiwan; the ROC retains control over the Taiwan Area, and its political status remains disputed. The ROC is recorded as a founding member of both the League of Nations and the United Nations, and previously held a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council until 1971, when the PRC took China's seat in the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758. It was also a member of the Universal Postal Union and the International Olympic Committee. The ROC claimed 11.4 million km2 (4.4 million sq mi) of territory,[2] and its population of 541 million in 1949 made it the most populous country in the world.

The Republic of China was officially proclaimed on 1 January 1912 by revolutionaries under Sun Yat-sen, the ROC's founder and provisional president of the new republic, following the success of the 1911 Revolution. Puyi, the final Qing emperor, abdicated on 12 February 1912. Sun served briefly before handing the presidency to Yuan Shikai, the leader of the Beiyang Army. Yuan's Beiyang government quickly became authoritarian and exerted military power over the administration; in 1915, Yuan attempted to replace the Republic with his own imperial dynasty until popular unrest forced him to back down. When Yuan died in 1916, the country fragmented between local commanders of the Beiyang Army, beginning the Warlord Era defined by decentralized conflicts between rival cliques. At times, the most powerful of these cliques used their control of Beijing to assert claims to govern the entire Republic.

Meanwhile, the KMT under Sun attempted multiple times to establish a rival national government in Guangzhou, eventually taking the city with the help of weapons, funding, and advisors from the Soviet Union under the condition that the KMT form the First United Front with the CCP. CCP members joined the KMT and the two parties cooperated to build a revolutionary base in Guangzhou, from which Sun planned to launch a campaign to reunify China. Sun's death in 1925 precipitated a power struggle that eventually resulted in the rise of General Chiang Kai-shek to KMT chairmanship. Chiang led the successful Northern Expedition from 1926 to 1928, benefitting from strategic alliances with warlords and the help of Soviet military advisors. By 1927, Chiang felt secure enough to end the alliance with the Soviets and purged the Communists from the KMT. In 1928, the last major warlord pledged allegiance to the KMT's Nationalist government in Nanjing. Chiang subsequently ruled the country as a one-party state (Dang Guo) under the KMT, receiving international recognition as the representative of China.[3]

While there was relative prosperity during the Nanjing decade (1927–1937), the ROC faced serious threats from within and without. After being severely weakened by the purge, the CCP gradually rebuilt its strength by organizing peasants in the countryside. In addition, warlords who resented Chiang's consolidation of power led several uprisings, most significantly the Central Plains War. In 1931, the Japanese invaded Manchuria, followed by a series of smaller encroachments and ultimately a full-scale invasion of China in 1937. World War II devastated China, leading to enormous loss of life and material destruction. War with Japan continued until their surrender in September 1945, after which Taiwan was placed under Chinese administration. Civil war then resumed, and the CCP's People's Liberation Army began to gain upper hand in 1948 over a larger and better-armed Republic of China Armed Forces due to better tactics and corruption within the ROC leadership. The CCP proclaimed the People's Republic of China in October 1949, though remnants of the ROC government would persist in mainland China until late 1951.

Name

[edit]The Republic of China's first president, Sun Yat-sen, chose Zhōnghuá Mínguó (中華民國; 'Chinese People's State') as the country's official Chinese name. The name was derived from the language of the Tongmenghui's 1905 party manifesto, which proclaimed that the four goals of the Chinese revolution were "to expel the Manchu rulers, revive China (Zhōnghuá), establish a people's state (mínguó), and distribute land equally among the people."[c][4] On 15 July 1916, in his welcoming speech to the Cantonese delegates in Shanghai, Sun explained why the term mínguó (民國; 'people's country') was chosen over the Japanese-derived gònghéguó (共和國).[5][6] He associated the label gònghé (共和) with the limiting and authoritarianism-prone Euro-American models of representative republicanism. What he strived for was a more grass-roots model, which he termed zhíjiē mínquán (直接民權; 'direct people's rights'), and which he thought would allow more checks and balances by the people. Later on 20 October 1923, at a national conference for youths in Guangzhou, to explain the core idea behind mínguó (民國; 'people's country'), he pithily compared the phrase "Empire of China" (中華帝國; Zhōnghuá Dìguó; 'Chinese Emperor's Country') to "Republic of China" (中華民國; Zhōnghuá Mínguó; 'Chinese People's Country') in the form of a parallelism: an emperor's country is ruled by only one emperor (帝國是以皇帝一人為主), a people's country is ruled by all four hundred million people (民國是以四萬萬人為主).[6] Both the "Beiyang government" (from 1912 to 1928), and the "Nationalist government" (from 1928 to 1949) used the name "Republic of China" as their official name.[7] In Chinese, the official name was often shortened to Zhōngguó (中國; 'Middle Country'), Mínguó (民國; 'People's Country'), or Zhōnghuá (中華; 'Middle Huaxia').[8][9][10]

The choice of the term mínguó (民國; 'people's country'; "republic") in 1912, as well as its similar semantic formation to dìguó (帝國; 'emperor's country'; "empire"), may have influenced the choice of the Korean term minguk (민국/民國) by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (founded in 1919 within the Republic of China), which replaced Daehan Jeguk (대한제국/大韓帝國) with Daehan Minguk (대한민국/大韓民國).[11] Today, the Republic of China (中華民國) and Republic of Korea (大韓民國) are unique in the choice of the term 民國 ('people's country') as an equivalent to "republic" in other languages.[11]

The country was in English known at the time as "the Republic of China" or simply "China".

In China today, the period from 1912 to 1949 is often called the "Republican Era" (simplified Chinese: 民国时期; traditional Chinese: 民國時期), because from the Chinese government's perspective the ROC ceased to exist in 1949.[12][13][14][15] In Taiwan, these years are called the "Mainland period" (大陸時期; 大陆时期), since it was when the ROC was based on the mainland.[16]

History

[edit]A republic was formally established on 1 January 1912 following the Xinhai Revolution, which itself began with the Wuchang uprising on 10 October 1911, successfully overthrowing the Qing dynasty and ending over two thousand years of imperial rule in China.[17] From its founding until 1949, the republic was based on mainland China. Central authority waxed and waned in response to warlordism (1915–1928), a Japanese invasion (1937–1945), and a full-scale civil war (1927–1949), with central authority strongest during the Nanjing Decade (1927–1937), when most of China came under the control of the authoritarian, one-party military dictatorship of the nationalist Kuomintang party (KMT).[18] Neither the Nanjing government nor the earlier Beiyang government succeeded in consolidating governance in rural China.[19]: 71

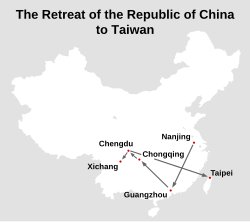

In 1945, at the end of World War II, the Empire of Japan surrendered control of Taiwan and its island groups to the Allies; and Taiwan was placed under the Republic of China's administrative control. The communist takeover of mainland China in 1949, after the Chinese Civil War, left the ruling Kuomintang with control over only Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and other minor islands. With the loss of the mainland, the ROC government retreated to Taiwan and the KMT declared Taipei the provisional capital.[20] Meanwhile, the CCP took over all of mainland China[21][22] and founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing.

1912–1916: Founding

[edit]

In 1912, after over two thousand years of dynastic rule, a republic was established to replace the monarchy.[17] The Qing dynasty that preceded the republic had experienced instability throughout the 19th century and suffered from both internal rebellion and foreign imperialism.[23] A program of institutional reform proved too little and too late. Only the lack of an alternative regime prolonged the monarchy's existence until 1912.[24][25]

The Chinese Republic grew out of the Wuchang Uprising against the Qing government, on 10 October 1911, which is now celebrated annually as the ROC's national day, also known as "Double Ten Day". Sun Yat-sen had been actively promoting revolution from his bases in exile.[26] He then returned and on 29 December, Sun Yat-sen was elected president by the Nanjing assembly,[27] which consisted of representatives from seventeen provinces. On 1 January 1912, he was officially inaugurated and pledged "to overthrow the despotic government led by the Manchu, consolidate the Republic of China and plan for the welfare of the people".[28] Sun's new government lacked military strength. As a compromise, he negotiated with Yuan Shikai the commander of the Beiyang Army, promising Yuan the presidency of the republic if he were to remove the Qing emperor by force. Yuan agreed to the deal.[29] On 12 February 1912, regent Empress Dowager Longyu signed the abdication decree on behalf of Puyi, ending several millennia of monarchical rule.[30] In 1913, elections were held for provincial assemblies, which would then chose delegates for a new National Assembly. The Kuomintang emerged as the formal political party that replaced the revolutionary organization Tongmenghui, and at the 1913 elections, it won the largest share of seats in both houses of the National Assembly and in some provincial assemblies.[31] Song Jiaoren led the Kuomintang Party to electoral victories by fashioning his party's program to appeal to the gentry, landowners, and merchants. Song was assassinated on 20 March 1913, at the behest of Yuan Shikai.[32]

Yuan was elected president of the ROC in 1913.[23][33] He ruled by military power and ignored the republican institutions established by his predecessor, threatening to execute Senate members who disagreed with his decisions. He soon dissolved the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) party, banned "secret organizations" (which implicitly included the KMT), and ignored the provisional constitution. Ultimately, Yuan declared himself Emperor of China in 1915.[34] The new ruler of China tried to increase centralization by abolishing the provincial system; however, this move angered the gentry along with the provincial governors, who were usually military men.[citation needed]

1916–1927: Warlord Era

[edit]Yuan's changes to government caused many provinces to declare independence and become warlord states. Increasingly unpopular and deserted by his supporters, Yuan abdicated in 1916 and died of natural causes shortly thereafter.[35][36] China then declined into a period of warlordism. Sun, having been forced into exile, returned to Guangdong in the south in 1917 and 1922, with the help of warlords, and set up successive rival governments to the Beiyang government in Beijing, having re-established the KMT in October 1919. Sun's dream was to unify China by launching an expedition against the north. However, he lacked the military support and funding to turn it into a reality.[37]

Meanwhile, the Beiyang government struggled to hold onto power, and an open and wide-ranging debate evolved regarding how China should confront the West. In 1919, a student protest against the government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, considered unfair by Chinese intellectuals, led to the May Fourth movement, whose demonstrations were against the danger of spreading Western influence replacing Chinese culture. It was in this intellectual climate that Marxist thought began to spread. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded in 1921.[38]

After Sun's death in March 1925, Chiang Kai-shek became the leader of the Kuomintang. In 1926, Chiang led the Northern Expedition with the intention of defeating the Beiyang warlords and unifying the country. Chiang received the help of the Soviet Union and the CCP. However, he soon dismissed his Soviet advisers, being convinced that they wanted to get rid of the KMT and take control.[39] Chiang decided to purge the Communists, massacring thousands in Shanghai. At the same time, other violent conflicts were taking place in China: in the South, where the CCP had superior numbers, Nationalist supporters were being massacred.[citation needed]

1927–1937: Nanjing decade

[edit]

Chiang Kai-shek pushed the CCP into the interior and established a government, with Nanjing as its capital, in 1927.[40] By 1928, Chiang's army overthrew the Beiyang government and unified the entire nation, at least nominally, beginning the Nanjing decade.[41]

Sun Yat-sen envisioned three phases for the KMT rebuilding of China – military rule and violent reunification; political tutelage; and finally a constitutional democracy.[42] In 1930, after seizing power and reunifying China by force, the "tutelage" phase started with the promulgation of a provisional constitution.[43] In an attempt to distant themselves from the Soviets, the Chinese government sought assistance from Germany.

According to Lloyd Eastman, Chiang Kai-shek was influenced by European fascist movements, and he launched the Blue shirts and the New Life Movement in imitation of them, in an effort to counter the growth of Mao's communism as well as resist both Western and Japanese imperialism.[44] According to Stanley Payne, however, Chiang's KMT was "normally classified as a multi-class populist or 'nation-building' party but not a fitting candidate for fascism (except by old-line Communists)." He also stated that, "Lloyd Eastman has called the Blue Shirts, whose members admired European fascism and were influenced by it, a Chinese fascist organization. This is probably an exaggeration. The Blue Shirts certainly exhibited some of the characteristics of fascism, as did many nationalist organizations around the world, but it is not clear that the group possessed the full qualities of an intrinsic fascist movement....The Blue Shirts probably had some affinity with and for fascism, a common feature of nationalisms in crisis during the 1930s, but it is doubtful that they represented any clear-cut Asian variant of fascism."[45]

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (March 2024) |

Still other historians have noted that Chiang and the KMT's exact ideology itself was very complex and oscillated over time, with different factions of his government cooperating with both the Soviets and Germans as they saw fit, and that Chiang eventually became disillusioned with the Blue Shirts, which officially disbanded by 1938,[46][47] something Payne also mentions as "possibly because of competition with the KMT itself."[48] Some have also noted that in contrast to older historians from decades ago, Chiang's efforts have been increasingly seen by newer Western and Chinese historians alike as an arguably necessary if austere part of the complicated nation-building process in China during his time, especially given the wide range of both domestic and foreign challenges it faced on many different concurrent fronts.[49][50][51]

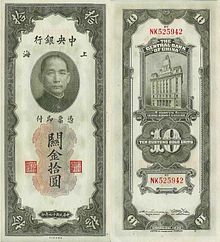

Several major government institutions were founded during this period, including the Academia Sinica and the Central Bank of China. In 1932, China sent its first team to the Olympic Games. Campaigns were mounted and laws passed to promote the rights of women. In the 1931 Civil Code, women were given equal inheritance rights, banned forced marriage and gave women the right to control their own money and initiate divorce.[52] No nationally unified women's movement could organize until China was unified under the Kuomintang Government in Nanjing in 1928; women's suffrage was finally included in the new Constitution of 1936, although the constitution was not implemented until 1947.[53] Addressing social problems, especially in remote villages, was aided by improved communications. The Rural Reconstruction Movement was one of many that took advantage of the new freedom to raise social consciousness.[citation needed] The Nationalist government published a draft constitution on 5 May 1936.[54]

Continual wars plagued the government. Those in the western border regions included the Kumul Rebellion, the Sino-Tibetan War, and the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang. Large areas of China proper remained under the semi-autonomous rule of local warlords such as Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan, provincial military leaders, or warlord coalitions.[41] Nationalist rule was strongest in the eastern regions around the capital Nanjing. The Central Plains War in 1930, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, and the Red Army's Long March in 1934 led to more power for the central government, but there continued to be foot-dragging and even outright defiance, as in the Fujian Rebellion of 1933–1934.[citation needed]

Reformers and critics pushed for democracy and human rights, but the task seemed difficult if not impossible. The nation was at war and divided between Communists and Nationalists. Corruption and lack of direction hindered reforms. Chiang told the State Council: "Our organization becomes worse and worse... many staff members just sit at their desks and gaze into space, others read newspapers and still others sleep."[55]

1937–1945: Second Sino-Japanese War

[edit]

Few Chinese had any illusions about Japanese desires on China. Hungry for raw materials and pressed by a growing population, Japan initiated the seizure of Manchuria in September 1931, and established the former emperor Puyi as head of the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932. The loss of Manchuria, and its potential for industrial development and war industries, was a blow to the Kuomintang economy. The League of Nations, established at the end of World War I, was unable to act in the face of Japanese defiance.[citation needed]

The Japanese began to push south of the Great Wall into northern China and the coastal provinces. Chinese fury against Japan was predictable, but anger was also directed against Chiang and the Nanjing government, which at the time was more preoccupied with anti-Communist extermination campaigns than with resisting the Japanese invaders. The importance of "internal unity before external danger" was forcefully brought home in December 1936, when Chiang Kai-shek was kidnapped by Zhang Xueliang and forced to ally with the Communists against the Japanese in the Second United Front, an event now known as the Xi'an Incident.[citation needed]

Chinese resistance stiffened after 7 July 1937, when a clash occurred between Chinese and Japanese troops outside Beijing near the Marco Polo Bridge. This skirmish led to open, although undeclared, warfare between China and Japan. Shanghai fell after a three-month battle during which Japan suffered extensive casualties in both its army and navy. Nanjing fell in December 1937, which was followed by mass murders and rapes known as the Nanjing Massacre. The national capital was briefly at Wuhan, then removed in an epic retreat to Chongqing, the seat of government until 1945. In 1940, the Japanese set up the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime, with its capital in Nanjing, which proclaimed itself the legitimate "Republic of China" in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek's government, although its claims were significantly hampered due to its being a puppet state controlling limited amounts of territory.[citation needed]

The United Front between the Kuomintang and the CCP had salutary effects for the beleaguered CCP, despite Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions and the rich Yangtze River valley in central China. After 1940, conflicts between the Kuomintang and Communists became more frequent in the areas not under Japanese control. The Communists expanded their influence wherever opportunities presented themselves through mass organizations, administrative reforms and the land- and tax-reform measures favoring the peasants and, the spread of their organizational network, while the Kuomintang attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence. Meanwhile, northern China was infiltrated politically by Japanese politicians in Manchukuo using facilities such as the Manchukuo Imperial Palace.[citation needed]

After its entry into the Pacific War during World War II, the United States became increasingly involved in Chinese affairs. As an ally, it embarked in late 1941 on a program of massive military and financial aid to the hard-pressed Nationalist Government. In January 1943, both the United States and the United Kingdom led the way in revising their unequal treaties with China from the past.[56][57] Within a few months a new agreement was signed between the United States and the Republic of China for the stationing of American troops in China as part of the common war effort against Japan. The United States sought unsuccessfully to reconcile the rival Kuomintang and Communists, to make for a more effective anti-Japanese war effort. In December 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1880s, and subsequent laws, enacted by the United States Congress to restrict Chinese immigration into the United States were repealed. The wartime policy of the United States was meant to help China become a strong ally and a stabilizing force in postwar East Asia. During the war, China was one of the Big Four Allies, and later one of the Four Policemen, which was a precursor to China having a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.[58]

In August 1945, with American help, Nationalist troops moved to take the Japanese surrender in North China. The Soviet Union—encouraged to invade Manchuria to hasten the end of the war and allowed a Soviet sphere of influence there as agreed to at the Yalta Conference in February 1945—dismantled and removed more than half the industrial equipment left there by the Japanese. Although the Chinese had not been present at Yalta, they had been consulted and had agreed to have the Soviets enter the war, in the belief that the Soviet Union would deal only with the Kuomintang government. However, the Soviet presence in northeast China enabled the Communists to arm themselves with equipment surrendered by the withdrawing Japanese army.[citation needed]

1945–1949: Defeat in the Chinese Civil War

[edit]In 1945, after the end of the war, the Nationalist Government moved back to Nanjing. The Republic of China emerged from the war nominally a great military power but actually a nation economically prostrate and on the verge of all-out civil war. The problems of rehabilitating the formerly Japanese-occupied areas and of reconstructing the nation from the ravages of a protracted war were staggering. The economy deteriorated, sapped by the military demands of foreign war and internal strife, by spiraling inflation, and by Nationalist profiteering, speculation, and hoarding. Starvation came in the wake of the war, and millions were rendered homeless by floods and unsettled conditions in many parts of the country.[citation needed]

On 25 October 1945, following the surrender of Japan, the administration of Taiwan and Penghu Islands were handed over from Japan to China.[59] After the end of the war, United States Marines were used to hold Beijing and Tianjin against a possible Soviet incursion, and logistic support was given to Kuomintang forces in north and northeast China. To further this end, on 30 September 1945 the 1st Marine Division, charged with maintaining security in the areas of the Shandong Peninsula and the eastern Hebei, arrived in China.[60]

In January 1946, through the mediation of the United States, a military truce between the Kuomintang and the Communists was arranged, but battles soon resumed. Public opinion of the administrative incompetence of the Nationalist government was incited by the Communists during the nationwide student protest against the mishandling of the Shen Chong rape case in early 1947 and during another national protest against monetary reforms later that year. The United States—realizing that no American efforts short of large-scale armed intervention could stop the coming war—withdrew Gen. George Marshall's American mission. Thereafter, the Chinese Civil War became more widespread; battles raged not only for territories but also for the allegiance of sections of the population. The United States aided the Nationalists with massive economic loans and weapons but no combat support.[citation needed]

Belatedly, the Republic of China government sought to enlist popular support through internal reforms. However, the effort was in vain, because of rampant government corruption and the accompanying political and economic chaos. By late 1948 the Kuomintang position was bleak. The demoralized and undisciplined National Revolutionary Army proved to be no match for the Communists' motivated and disciplined People's Liberation Army. The Communists were well established in the north and northeast. Although the Kuomintang had an advantage in numbers of men and weapons, controlled a much larger territory and population than their adversaries, and enjoyed considerable international support, they were exhausted by the long war with Japan and in-fighting among various generals. They were also losing the propaganda war to the Communists, with a population weary of Kuomintang corruption and yearning for peace.[citation needed]

In January 1949, Beiping was taken by the Communists without a fight, and its name changed back to Beijing. Following the capture of Nanjing on 23 April, major cities passed from Kuomintang to Communist control with minimal resistance, through November. In most cases the surrounding countryside and small towns had come under Communist influence long before the cities. Finally, on 1 October 1949, Communists led by Mao Zedong founded the People's Republic of China. Chiang Kai-shek declared martial law in May 1949, whilst a few hundred thousand Nationalist troops and two million refugees, predominantly from the government and business community, fled from mainland China to Taiwan. There remained in China itself only isolated pockets of resistance. On 7 December 1949, Chiang proclaimed Taipei the temporary capital of the Republic of China.[citation needed]

During the Chinese Civil War both the Nationalists and Communists carried out mass atrocities, with millions of non-combatants killed by both sides.[61] Benjamin Valentino has estimated atrocities in the civil war resulted in the death of between 1.8 million and 3.5 million people between 1927 and 1949, including deaths from forced conscription and massacres.[62]

Government

[edit]The first Republic of China national government was established on 1 January 1912, in Nanjing, with a constitution stating Three Principles of the People, which state that "[the ROC] shall be a democratic republic of the people, to be governed by the people and for the people."[63]

Sun Yat-sen was the provisional president. Delegates from the provinces sent to confirm the government's authority formed the first parliament in 1913. The power of this government was limited, with generals controlling both the central and northern provinces of China, and short-lived. The number of acts passed by the government was few and included the formal abdication of the Qing dynasty and some economic initiatives. The parliament's authority soon became nominal: violations of the Constitution by Yuan were met with half-hearted motions of censure. Kuomintang members of parliament who gave up their membership in the KMT were offered 1,000 pounds. Yuan maintained power locally by sending generals to be provincial governors or by obtaining the allegiance of those already in power.[citation needed]

When Yuan died, the parliament of 1913 was reconvened to give legitimacy to a new government. However, the real power passed to military leaders, leading to the warlord period. The impotent government still had its use; when World War I began, several Western powers and Japan wanted China to declare war on Germany, to liquidate German holdings in China.[citation needed]

In February 1928, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 2nd Kuomintang National Congress, held in Nanjing, passed the Reorganization of the Nationalist Government Act. This act stipulated that the Nationalist Government was to be directed and regulated under the Central Executive Committee of the Kuomintang, with the Committee of the Nationalist Government being elected by the KMT Central Committee. Under the Nationalist Government were seven ministries—Interior, Foreign Affairs, Finance, Transport, Justice, Agriculture and Mines, and Commerce, in addition to institutions such as the Supreme Court, Control Yuan, and the General Academy.[citation needed]

With the promulgation of the Organic Law of the Nationalist Government in October 1928, the government was reorganized into five different branches, or yuan, namely the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Examination Yuan as well as the Control Yuan. The Chairman of the National Government was to be the head-of-state and commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army. Chiang Kai-shek was appointed as the first chairman, a position he would retain until 1931. The Organic Law also stipulated that the Kuomintang, through its National Congress and Central Executive Committee, would exercise sovereign power during the period of "political tutelage", that the KMT's Political Council would guide and superintend the Nationalist Government in the execution of important national affairs, and that the Political Council has the power to interpret or amend the Organic Law.[64]

Shortly after the Second Sino-Japanese War, a long-delayed constitutional convention was summoned to meet in Nanjing in May 1946. Amidst heated debate, this convention adopted many constitutional amendments demanded by several parties, including the KMT and the Communist Party, into the Constitution. This Constitution was promulgated on 25 December 1946 and came into effect on 25 December 1947. Under it, the Central Government was divided into the presidency and the five yuans, each responsible for a part of the government. None was responsible to the other except for certain obligations such as the president appointing the head of the Executive Yuan. Ultimately, the president and the yuans reported to the National Assembly, which represented the will of the citizens.[citation needed]

Under the new constitution the first elections for the National Assembly occurred in January 1948, and the assembly was summoned to meet in March 1948. It elected the president of the republic on 21 March 1948, formally bringing an end to the KMT party rule started in 1928, although the president was a member of the KMT. These elections, though praised by at least one US observer, were poorly received by the Communist Party, which would soon start an open, armed insurrection.[citation needed]

Foreign relations

[edit]Before the Nationalist government was ousted from the mainland, the Republic of China had diplomatic relations with 59 countries[citation needed], including Australia, Canada, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, France, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Panama, Siam, the Soviet Union, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Holy See. The Republic of China was able to maintain most of these diplomatic ties, at least initially following the retreat to Taiwan. Chiang Kai-shek had vowed to quickly return and "liberate" the mainland,[65][66] an assurance that became a cornerstone of the ROC's post 1949 foreign policy.

The ROC did try to participate in a variety of entities for the international community including the League of Nations along with its successor the United Nations[67] and the Olympic Games.[68] It was hoped by the government that participating in the Olympic Games this could give more legitimacy to the country in the eyes of the international community and "sports could also cultivate modern citizens and a strong nation". The Republic of China sent athletes to the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin and the 1948 Summer Olympics but no athletes won any medals. For 1928 a single athlete was sent. Although athletes were sent to the 1924 games they did not participate in the games.[69][70]

League of Nations

[edit]The Republic of China was a member of the League of Nations and participated until it was dissolved. Those in the country's foreign relations were among the most stable of those working in the government in terms of composition. The ROC was a non-permanent member of the League Council for the League of Nations being a non-permanent member of the League Council from: 1921–1923, 1926–1928, 1931–1932, 1934, and 1936. Although the ROC lobbied to be a permanent member of the League Council it never became one. At the League of Nations, China wanted to see the unequal treaties revised. The ROC thought that by being in the League they could improve their international standing.[67]

United Nations

[edit]Under the Charter of the United Nations, the Republic of China was entitled to a permanent seat on the UN Security Council (UNSC).[71][72] Though multiple objections were raised that the seat belonged to the lawful government of China, which had to many become the PRC even arguably prior to the official conclusion of the Chinese Civil War,[d][73][74] the ROC retained the permanent seat reserved for China on the UNSC until 1971 when it was supplanted by the PRC.[75]

Administrative divisions

[edit]-

Rand McNally map of the Republic of China in 1914, after Mongolia declared its independence

-

Map of the first-level administrative divisions of the Republic of China in law (1945)

| Name | Traditional Chinese |

Pinyin | Abbreviation | Capital | Chinese | Modern equivalent (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provinces | ||||||

| Andong | 安東 | Āndōng | 安 ān | Tonghua | 通化 | [note 1] |

| Anhui | 安徽 | Ānhuī | 皖 wǎn | Hefei | 合肥 | |

| Chahar | 察哈爾 | Cháhār | 察 chá | Zhangyuan (Zhangjiakou) | 張垣(張家口) | [note 2] |

| Zhejiang | 浙江 | Zhèjiāng | 浙 zhè | Hangzhou | 杭州 | |

| Fujian | 福建 | Fújiàn | 閩 mǐn | Fuzhou | 福州 | [note 3] |

| Hebei | 河北 | Héběi | 冀 jì | Qingyuan (Baoding) | 清苑(保定) | |

| Heilongjiang | 黑龍江 | Hēilóngjiāng | 黑 hēi | Bei'an | 北安 | |

| Hejiang | 合江 | Héjiāng | 合 hé | Jiamusi | 佳木斯 | [note 4] |

| Henan | 河南 | Hénán | 豫 yù | Kaifeng | 開封 | |

| Hubei | 湖北 | Húběi | 鄂 è | Wuchang | 武昌 | |

| Hunan | 湖南 | Húnán | 湘 xiāng | Changsha | 長沙 | |

| Xing'an | 興安 | Xīng'ān | 興 xīng | Hailar (Hulunbuir) | 海拉爾(呼倫貝爾) | [note 5] |

| Jehol (Rehe) | 熱河 | Rèhé | 熱 rè | Chengde | 承德 | [note 6] |

| Gansu | 甘肅 | Gānsù | 隴 lǒng | Lanzhou | 蘭州 | |

| Jiangsu | 江蘇 | Jiāngsū | 蘇 sū | Zhenjiang | 鎮江 | |

| Jiangxi | 江西 | Jiāngxī | 贛 gàn | Nanchang | 南昌 | |

| Jilin | 吉林 | Jílín | 吉 jí | Jilin | 吉林 | |

| Guangdong | 廣東 | Guǎngdōng | 粵 yuè | Guangzhou | 廣州 | |

| Guangxi | 廣西 | Guǎngxī | 桂 guì | Guilin | 桂林 | |

| Guizhou | 貴州 | Guìzhōu | 黔 qián | Guiyang | 貴陽 | |

| Liaobei | 遼北 | Liáoběi | 洮 táo | Liaoyuan | 遼源 | [note 7] |

| Liaoning | 遼寧 | Liáoníng | 遼 liáo | Shenyang | 瀋陽 | |

| Ningxia | 寧夏 | Níngxià | 寧 níng | Yinchuan | 銀川 | |

| Nenjiang | 嫩江 | Nènjiāng | 嫩 nèn | Qiqihar | 齊齊哈爾 | [note 8] |

| Shanxi | 山西 | Shānxī | 晉 jìn | Taiyuan | 太原 | |

| Shandong | 山東 | Shāndōng | 魯 lǔ | Jinan | 濟南 | |

| Shaanxi | 陝西 | Shǎnxī | 陝 shǎn | Xi'an | 西安 | |

| Xikang | 西康 | Xīkāng | 康 kāng | Kangding | 康定 | [note 9] |

| Xinjiang | 新疆 | Xīnjiāng | 新 xīn | Dihua (Ürümqi) | 迪化(烏魯木齊) | |

| Suiyuan | 綏遠 | Suīyuǎn | 綏 suī | Guisui (Hohhot) | 歸綏(呼和浩特) | [note 10] |

| Songjiang | 松江 | Sōngjiāng | 松 sōng | Mudanjiang | 牡丹江 | [note 11] |

| Sichuan | 四川 | Sìchuān | 蜀 shǔ | Chengdu | 成都 | |

| Taiwan | 臺灣 | Táiwān | 臺 tái | Taipei | 臺北 | [note 12] |

| Qinghai | 青海 | Qīnghǎi | 青 qīng | Xining | 西寧 | |

| Yunnan | 雲南 | Yúnnán | 滇 diān | Kunming | 昆明 | |

| Special Administrative Region | ||||||

| Hainan | 海南 | Hǎinán | 瓊 qióng | Haikou | 海口 | |

| Regions | ||||||

| Mongolia Area (Outer Mongolia) | 蒙古 | Ménggǔ | 蒙 méng | Kulun (now Ulaanbaatar) | 庫倫 | [note 13] |

| Tibet Area (Tibet) | 西藏 | Xīzàng | 藏 zàng | Lhasa | 拉薩 | |

| Special Municipalities | ||||||

| Nanjing | 南京 | Nánjīng | 京 jīng | (Qinhuai District) | 秦淮區 | |

| Shanghai | 上海 | Shànghǎi | 滬 hù | (Huangpu District) | 黄浦區 | |

| Harbin | 哈爾濱 | Hā'ěrbīn | 哈 hā | (Nangang District) | 南崗區 | |

| Shenyang | 瀋陽 | Shěnyáng | 瀋 shěn | (Shenhe District) | 瀋河區 | |

| Dalian | 大連 | Dàlián | 連 lián | (Xigang District) | 西崗區 | |

| Beijing (while capital) | 北平 | Běipíng | 平 píng | (Xicheng District) | 西城區 | |

| Tianjin | 天津 | Tiānjīn | 津 jīn | (Heping District) | 和平區 | |

| Chongqing | 重慶 | Chóngqìng | 渝 yú | (Yuzhong District) | 渝中區 | |

| Hankou, Wuhan | 漢口 | Hànkǒu | 漢 hàn | (Jiang'an District) | 江岸區 | |

| Guangzhou | 廣州 | Guǎngzhōu | 穗 suì | (Yuexiu District) | 越秀區 | |

| Xi'an | 西安 | Xī'ān | 安 ān | (Weiyang District) | 未央區 | |

| Qingdao | 青島 | Qīngdǎo | 膠 jiāo | (Shinan District) | 市南區 | |

- ^ Now part of Jilin and Liaoning

- ^ Now part of Inner Mongolia and Hebei

- ^ Kinmen and Matsu Islands retained by the ROC. Provincial government suspended in 2019.

- ^ Now part of Heilongjiang

- ^ Now part of Heilongjiang and Jilin

- ^ Now part of Hebei, Liaoning, and Inner Mongolia

- ^ Now mostly part of Inner Mongolia

- ^ The province was abolished in 1950 and incorporated into Heilongjiang province.

- ^ Now part of Tibet and Sichuan

- ^ Now part of Inner Mongolia

- ^ Now part of Heilongjiang

- ^ Taiwan was only under ROC control after the surrender of Japan. Government suspended since 2018.

- ^ Now part of the State of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. As the successor of the Qing dynasty, the Government of the Republic of China claimed Outer Mongolia before 1946, and for a short time under the Beiyang government occupied it. The Nationalist government officially recognized Mongolia's independence after the 1945 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship due to pressure from the Soviet Union.[77]

Nobility

[edit]The Republic of China retained hereditary nobility like the Han Chinese nobles Duke Yansheng and Celestial Masters and Tusi chiefdoms like the Chiefdom of Mangshi, Chiefdom of Yongning, who continued possessing their titles in the Republic of China from the previous dynasties.[citation needed]

Military

[edit]Military conscription was practiced in the Republic of China starting in March 1936 after a 1933 law was passed. All males between 18 and 45 were required to register for as citizen-soldiers where they would learn how to use weapons, build fortifications, execute basic orders, conduct reconnaissance and do liaison work. Able-bodied men from 20 to 25 were required to serve in the military for 3 years before becoming reservists which they would remain as until they were 45. Those being exempt from serving in the military were: only sons, high school graduates and above, students who were in high school or above, could not meet physical standards, "suffered from incurable diseases" and had special governmental appointments. One could also get a deferment if they were civil servants, "could not recover from any disease within months", teachers, "those who were not clear of suspicion for criminal offenses" or where half the sons in a given family were active duty soldiers. Those barred from military service were people who were serving a life sentence or "deprived of political rights".[78]

Army

[edit]

The Republic of China's military initially consisted of the decentralized forces of the former Qing dynasty, with the most modern and organized being the Beiyang Army, before it split into factions that attacked each other.[79][80] During the Second Revolution in 1913, as the president of the republic, Yuan Shikai used the Beiyang Army to defeat provincial forces opposed to him and to extend his control over north China and other provinces as far south as the Yangtze River. This also led to the expansion of the size of the Beiyang Army, and an effort was made by Yuan to reduce provincial armies in areas he controlled,[81][82] though they were not completely disbanded.[83] Yuan ended the Qing practice of frequently rotating officers among command positions in the Beiyang divisions, which led to the subordinates developing personal loyalty to their commanders, whose units became their power base. He maintained control over the Beiyang Army by providing the division commanders with the patronage of the presidency, and had them keep each other in check. Yuan was unable to completely reorganize the fragmented command structure of China's military to be more of a bureaucratic institution under the direct control of the central government.[84] After Yuan's death in 1916, the Beiyang Army split among different factions led by his generals that rivaled each other. Though they continued to control the central government in Beijing, they were unable to take over the south.[85] The southern warlords had their own armies but they were also divided by conflicts among themselves.[86] Despite the breakdown of centralized leadership, some military schools established during the Qing dynasty continued to function during the warlord era, including the Baoding Military Academy, which graduated the majority of officers that served in warlord armies and many that later became Nationalist officers.[79][87]

Sun Yat-sen created a new government in 1917 as an alternative to the Beiyang, but he did not have the military power to control the southern warlords.[88] Therefore, the National Revolutionary Army was established by Sun in 1924 in Guangdong with the goal of reunifying China under the Kuomintang, with Soviet advisors and equipment.[89] To avoid the problems of warlord armies, the NRA was under the political and ideological control of a party, the KMT, and included party representatives in its ranks.[90] After Sun's death in 1925, Chiang Kai-shek led the Nationalist Army in its first campaign against less organized warlord forces from 1926 to 1928, becoming known as the Northern Expedition.[91] After the success of the Northern Expedition the National Revolutionary Army was seen as China's national army, despite warlords still controlling parts of the country. During the next decade the army was increased in size from 250,000 to around two million, organized into 200 divisions. In the 1930s a small number of these divisions received training from German instructors, as well as modern uniforms and weapons, as part of the process of creating a professional army.[92] The Whampoa Military Academy had been established by Sun Yat-sen with Soviet assistance to provide officers for the KMT army,[89] and in 1928 it was moved to Nanjing to become the Central Military Academy, where its size and training program was expanded by the Germans. But these German-trained forces represented a small part of the total KMT army,[92] numbering about 40 divisions.[93]

When the war between Japan and China broke out in 1937, Chiang Kai-shek deployed his best divisions to central China, where they took heavy losses during the Battle of Shanghai and the following retreat. Half of the officers that graduated from the Central Military Academy were killed in the first few months of fighting.[94] By 1941, the Chinese Nationalist Army had 3.8 million troops in 246 front-line divisions and 70 reserve divisions, though the majority of the divisions were under-strength and the troops were poorly trained. Many of these divisions were still more loyal to warlords than to Chiang Kai-shek. The U.S. also provided military assistance to China, planning to equip 30 divisions, but the prioritization of the European theater and the logistical difficulties of getting the supplies to China prevented these plans from being fully carried out.[93][95]

After the Battle of Wuhan in 1938, the Chinese Army tried to avoid direct large scale fighting with the Japanese.[94] Chiang also wanted to preserve his army instead of engaging in ground operations, despite pressure from the American leadership to go on the offensive.[96] It was not until early 1944 when Chiang agreed to launch a major offensive against Japanese forces in Burma to reopen the overland supply line to China, though it was unsuccessful. It took place around the same time as Japan's largest offensive since 1941, Operation Ichi-Go. The Japanese advanced rapidly in central and southeast China, as the Chinese Army still suffered from a lack of supplies, and by the start of 1945 they captured several U.S. air bases and created a direct connection to French Indochina.[97] In early 1945, Chinese and Allied troops in Burma succeeded in opening a land route to India, allowing more equipment to be sent to the Chinese, which they used to stop Japanese advances in southeast China by May. They were planning an offensive to retake control of a port in southern China when Japan surrendered.[98][99]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the armed forces of the CCP were nominally incorporated into the National Revolutionary Army, while remaining under separate command, but broke away to form the People's Liberation Army shortly after the end of the war. With the promulgation of the Constitution of the Republic of China in 1947 and the formal end of the KMT party-state, the National Revolutionary Army was renamed the Republic of China Armed Forces, with the bulk of its forces forming the Republic of China Army, which retreated to Taiwan in 1949 after their defeat in the Chinese Civil War. Units which surrendered and remained in mainland China were either disbanded or incorporated into the People's Liberation Army.[100]

Navy

[edit]

The Republic of China's Navy during between 1911 and 1949 was primarily composed of ships from the Qing Dynasty or ships obtained from foreign countries. As most threats to the Republic were on land from the warlords and the Communists there was no interest in developing any maritime strategies. No significant efforts were made during this period to grow the navy because of China being in a state of general disarray. Sometimes warlords did use maritime forces but mainly as a way of supporting land combat.[101] When Sun Yat-sen established his constitutional protection government in Guangzhou in 1917, some of his early support came from the Chinese navy, represented by admirals Cheng Biguang and Lin Baoyi.[102] In 1926, Admiral Yang Shuzhuang led some elements of the Beiyang Fleet to defect to the National Revolutionary Army and became the head of the revolutionary navy on the Yangtze River.[103][104] One of Admiral Yang's subordinates was Chen Shaokuan,[103] who became the commander of the ROC Navy in 1932 and remained in that position until after the war with Japan. During the 1930s he organized the Chinese navy into the Central, Northeast, and Guangdong Fleets.[105][106]

Chiang Kai-shek announced in 1928 that it was his intention to build a large navy for China, but this goal was undermined by financial problems and other difficulties.[106] Many senior officers did not have modern naval training, and newer officers that were educated in Western countries were not promoted. When the war with Japan broke out, the majority of the Chinese fleet was used during the Battle of Shanghai to slow down the Japanese advance along the Yangtze River. Many ships were sunk by Japanese aircraft or were sunk deliberately by the Chinese to use as blockships in the Yangtze. By 1939 most of the Chinese navy had been destroyed, with one estimate claiming that over 100 of the navy's 120 ships in 1937 had been sunk. Some Chinese warships (notably the cruisers Ning Hai and Ping Hai) were later refloated and put into service by the Imperial Japanese Navy.[105] The building of a Chinese navy was no longer a priority during the rest of the war,[106] and in 1940 Chiang Kai-shek disbanded the Ministry of the Navy.[105]

In 1945, Chiang revived plans to create a modern Chinese Navy and asked the United States for assistance. The Nationalists received over 100 ships from the U.S. and its allied countries, as well as some captured Axis ships. Before the end of 1945 a navy training center was established in Qingdao by the U.S. Navy. The new navy was mainly used to transport troops and patrol the coastline during the Chinese Civil War.[107][108] In 1948, the former British cruiser HMS Aurora was gifted to China and was renamed Chongqing, becoming the flagship of the ROCN. In February 1949, as Chinese Communist forces advanced to the Yangtze River from the north, a mutiny of sailors occurred on Chongqing and the flagship defected to the Communists. This was followed in April by a mutiny of the entire fleet along the Yangtze, which was led by its commander to the other side. Because of this, 23 April 1949 is considered the founding date of the People's Liberation Army Navy.[109] At the end of the war the rest of the ROCN moved Nationalist troops from the mainland to Taiwan.[107]

The ROC Marine Corps was created from the former Naval Guard Corps, and consisted of two marine brigades, which were used during the war against Japan in several provinces before the corps was disbanded in 1946.[110] In 1947, a reorganized Republic of China Marine Corps was created by the commander of the Navy using select personnel from the Army.[111]

Air Force

[edit]

The Republic of China Air Force during the Second-Sino Japanese War was outmatched by the Japanese aviation forces. Foreign advisors from Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom came to China in the 1930s; while foreign aircraft were also imported from a variety of countries. With the beginning of the war they began to rely most heavily on the United States and Soviet Union for advisors. The low amount of planes being domestically produced would prove to be a hindrance.[112]

Beginning in 1929, the Nationalist government started expanding its air power to improve its position over warlords and the Communists. The ROC Air Force was formally established in April 1929, and that month the aviation department of the Ministry of War was separated as the National Aviation Administration, with General Chang We-chang as its head. He started a program of buying American aircraft, with the first, Vought Corsair planes, arriving in early 1930. The Chinese Air Force expanded from the first 12 Corsair planes in 1930 to a size of eight squadrons, with seven of bomber-observation planes and one of pursuit planes, in 1931, with a total of 40 to 50 aircraft. Several American pilots became advisors to China's air force and fought in battles against the Japanese or warlords.[113] The Nationalist Air Force had a role in the Central Plains War of 1930 by bombing cities, directing artillery, and observing warlord army defensive positions, and is credited with helping bring about a faster victory for Chiang Kai-shek's government. It had less success against the Japanese during the Shanghai Incident in 1932.[114]

In September 1932, the Central Aviation School was founded with the help of an American mission led by John Jouett, and its graduates included the majority of Chinese pilot officers by 1937. On his recommendation, the ROCAF was restructured, with a Ministry of Aviation equal to that of the Military and Navy Ministries being established under the Military Affairs Commission. Additional planes were purchased, and factories were also opened in China. As of 1936, the Chinese Air Force had 645 aircraft, and multiple factories and schools.[115]

When the war with Japan broke out in July 1937, much of the ROC Air Force was destroyed during the fighting in central China by December of that year. From 1938 to 1940 the Soviet Volunteer Group did much of the fighting against the Japanese, along with the remnants of the ROCAF.[116] The Soviets sent 885 planes to China over those years.[117]

Economy

[edit]

In the early years of the Republic of China, the economy remained unstable as the country was marked by constant warfare between different regional warlord factions. The Beiyang government in Beijing experienced constant changes in leadership, and this political instability led to stagnation in economic development until Chinese reunification in 1928 under the Kuomintang.[118] After this reunification, China entered a period of relative stability—despite ongoing isolated military conflicts and in the face of Japanese aggression in Shandong and Manchuria, in 1931—a period known as the "Nanjing Decade".[citation needed]

Chinese industries grew considerably from 1928 to 1931. While the economy was hit by the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931 and the Great Depression from 1931 to 1935, industrial output recovered to their earlier peak by 1936. This is reflected by the trends in Chinese GDP. In 1932, China's GDP peaked at 28.8 billion, before falling to 21.3 billion by 1934 and recovering to 23.7 billion by 1935.[119] By 1930, foreign investment in China totaled 3.5 billion, with Japan leading (1.4 billion) followed by the United Kingdom (1 billion). By 1948, however, the capital investment had halted and dropped to only 3 billion, with the US and Britain being the leading investors.[120]

However, the rural economy was hit hard by the Great Depression of the 1930s, in which an overproduction of agricultural goods lead to falling prices for China as well as an increase in foreign imports (as agricultural goods produced in western countries were "dumped" in China). In 1931, Chinese imports of rice amounted to 21 million bushels compared with 12 million in 1928. Other imports saw even more increases. In 1932, 15 million bushels of grain were imported compared with 900,000 in 1928. This increased competition lead to a massive decline in Chinese agricultural prices and thus the income of rural farmers. In 1932, agricultural prices were at 41 percent of 1921 levels.[121] By 1934, rural incomes had fallen to 57 percent of 1931 levels in some areas.[121]

In 1937, the Second Sino-Japanese War began with a Japanese invasion of China, and the resulting warfare laid waste to China. Most of the prosperous east coast was occupied by the Japanese, who committed atrocities such as the Nanjing massacre. In one anti-guerilla sweep in 1942, the Japanese killed up to 200,000 civilians in a month. The war was estimated to have killed between 20 and 25 million Chinese, and destroyed all that Chiang had built up in the preceding decade.[122] Development of industries was severely hampered after the war by devastating civil conflict as well as the inflow of cheap American goods. By 1946, Chinese industries operated at 20% capacity and had 25% of the output of pre-war China.[123]

One effect of the war with Japan was a massive increase in government control of industries. In 1936, government-owned industries were only 15% of GDP. However, the ROC government took control of many industries to fight the war. In 1938, the ROC established a commission for industries and mines to supervise and control firms, as well as instilling price controls. By 1942, 70% of Chinese industry was owned by the government.[124]

Following the surrender of Japan in World War II, Japanese Taiwan was placed under the control of the ROC. In the meantime, the KMT renewed its struggle with the communists. However, the corruption and hyperinflation as a result of trying to fight the civil war, resulted in mass unrest throughout the Republic[125] and sympathy for the communists. In addition, the communists' promise to redistribute land gained them support among the large rural population. In 1949, the communists captured Beijing and later Nanjing. The People's Republic of China was proclaimed on 1 October 1949. The Republic of China relocated to Taiwan where Japan had laid an educational groundwork.[126]

Transportation

[edit]China's infrastructure would grow dramatically during this period. The railroad network length grew from 9,600 kilometres (6,000 mi) in 1912 to 25,000 kilometres (16,000 mi) by 1945. The Shanxi warlord Yan Xishan was known for his strong commitment toward developing railroads. During the Nanjing decade the length of the highway network grew from 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) to 109,000 kilometres (68,000 mi) while growth was also seen in navigable waterways. In the early 1930s, a Sichuan warlord named Liu Xiang was strongly committed toward creating an entirely Chinese navigation company and eliminating foreign-owned companies in the Yangtze River basin.[127]

Communications

[edit]The Republic of China had a national postal system which began under the Qing Dynasty and carried over into the Republican period. The postal service did pull of Manchuria when the Japanese did invade it in 1931 and in Mongolia in 1924. The postal service continued to operate in other areas of the country even when they were taken by the Japanese and eventually began offering their services once again in Manchuria. In rural areas the postal service even offered free deliveries.[128]

Radio had been previously experimented with during the Qing Dynasty and work continued into the Republican era. Radio stations began appearing in the 1920s being mainly concentrated in Shanghai. The Kuomintang would create a national radio program, the Central China Broadcasting Station (CCBS). The CBBS held programs that related to the news, education and entertainment along with putting the news in difference dialects of Chinese. However, those who actually listened to the radio in China were predominantly in the urban areas .Most radios were foreign made and little were made domestically.[129]

Culture

[edit]Prior to the fall of the Qing dynasty, interaction and trade with western countries was more common in China than it had been in previous times. This led to greater cultural influence from the west in China. The culture of China and daily life within the country was disrupted from its previous state by the fall of dynastic rule. The Republic of China maintained the increase of western cultural influence in the country. Chinese intellectuals of the time were not unified in their opinions on the cultural changes occurring in the newly founded state. Some took progressive stances and advocated for Art Reform, while more conservative intellectuals believed China should maintain older Chinese traditions.[130]

Motion pictures were introduced to China in 1896. They were introduced through foreign film exhibitors in treaty ports like Shanghai and Hong Kong.[131]: 68 Chinese-made short melodrama and comedy films began emerging in 1913.[132]: 48 Chinese film production developed significantly in the 1920s.[132]: 48 Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, filmmaking in China was largely done by film studios and there was comparatively little small scale filmmaking.[132]: 62 Upscale movie theaters in China had contracts which required them to exclusively show Hollywood films, and thus as of the later 1920s, Hollywood films accounted for 90% of screen time in Chinese theaters.[132]: 64 After the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, a large number filmmakers left to join the War of Resistance, with many going to the Nationalist-controlled hinterlands to join the Nationalist film studios Central Motion Picture Studio or China Motion Picture Studio.[132]: 102 A smaller number went to Yan'an or Hong Kong.[132]: 102–103

During the Nanjing government, the ROC launched a cultural campaign promoting the "Arts of the Three Principles of the People."[19]: 120 It sought (mostly unsuccessfully) to attract cultural workers to create new propaganda works and more successfully established a censorship apparatus directed against unwelcome cultural products, especially left-wing artists and their works.[19]: 120–121

See also

[edit]- China–Soviet Union relations

- Economic history of China (1912–1949)

- History of China–United States relations to 1948

- Vice Premier of the Republic of China

- Project National Glory

Notes

[edit]- ^ The state did not cease to exist in 1949. The government was relocated from Nanjing to Taipei, where it remains today.

- ^ The state did not cease to exist in 1949. The government was relocated from Nanjing to Taipei, where it remains today.

- ^ Chinese: 驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權; pinyin: Qūchú dálǔ, huīfù Zhōnghuá, chuànglì mínguó, píngjūn dì quán

- ^ The relocation to Taiwan was initially intended to be a regrouping as the KMT had not actually been wholly defeated in the rest of China in 1949 and was initially able to hold onto pockets of Chinese territory on the mainland. After losing Hainan in 1950, most KMT holdouts were soon overrun, attempts to hold parts of the Chinese coast, especially that closest to Taiwan failed and rather than returning and reconquering – by the late 1950s the only presence the ROC had in mainland China was in the remote areas of western China's wilderness were a small number of KMT loyalists held out fighting a guerilla campaign that was gradually worn down.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dreyer, June Teufel (17 July 2003). The Evolution of a Taiwanese National Identity. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ 中華民國九十四年年鑑:第一篇 總論 第二章 土地 第二節 大陸地區 [Yearbook of the 94th Year of the Republic of China: Chapter 1 General Introduction, Chapter 2 Land Section, 2 Mainland Region]. Government Information Office, Executive Yuan, Republic of China (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Wang, Dong (1 October 2005). China's Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History. Lexington. ISBN 978-0-7391-5297-3 – via Google Books.

- ^ 計秋楓; 朱慶葆 (2001). Zhongguo jin dai shi 中國近代史. Vol. 1. Chinese University Press. p. 468. ISBN 9789622019874.

- ^ "中華民國之意義". Sun Yat-Sen Studies Database. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024.

諸君知中華民國之意義乎?何以不曰「中華共和國」,而必曰「中華民國」?此「民」字之意義,為僕研究十餘年之結果而得之者。歐美之共和國,創建遠在吾國之前。二十世紀之國,當含有創制之精神,不當自謂能效法於十八九世紀成法,而引為自足。共和政體為代表政體,世界各國,隸於此旗幟之下者,如希臘,則有貴族奴隸之堦級,直可稱之曰「專制共和」。如美國則已有十四省,樹直接民權之規模,而瑞士則全乎直接民權制度也。雖吾人今既易專制而成代議政體,然何可故步自封,落於人後。故今後國民當奮振全神於世界,發現一光芒萬丈之奇采,俾更進而底於直接民權之域。代議政體旗幟之下,吾民所享者,祇一種代議權。若底於直接民權,則有創制權、廢止權、退官權。但此種民權,不宜以廣漠之省境施行之,故當以縣為單位。地方財政完全由地方處理之,而分任中央之政費。其餘各種實業,則懲美國托拉斯之弊,而歸諸中央。如是數年,必有一莊嚴燦爛之中華民國發現於東大陸,駕諸世界共和國之上矣。

- ^ a b 黎民. "中華民國國號的來由和意義". 黄花岗杂志. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016.

- ^ Wright (2018).

- ^ "中华民国临时大总统对外宣言书". 孙中山故居纪念馆. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

抑吾人更有进者,民国与世界各国政府人民之交际,此后必益求辑睦。

- ^ 溫躍寬. 被西方誉成为的“民国黄金十年”. 憶庫. 2013-10-17 [2014-02-23](in Chinese).

- ^ 中华民国纪年也称“民国纪年”。

- ^ a b Lee, Junghwan (June 2013). "The History of Konghwa 共和 in Early Modern East Asia and Its Implications in the [Provisional] Constitution of the Republic of Korea". Acta Koreana. 16 (1).

- ^ "Exploring Chinese History :: Database Catalog :: Biographical Database :: Republican Era- (1912–1949)". Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "民國時期(1911–1949)的目錄與學者數據庫". Harvard University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ 吳展良. "民国时期的启蒙与批判启蒙". National Taiwan University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "民国时期期刊全文数据库(1911~1949)". 全国报刊索引. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Joachim, Martin D. (1993). Languages of the World: Cataloging Issues and Problems. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781560245209. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ a b China, Fiver thousand years of History and Civilization. City University Of Hong Kong Press. 2007. p. 116. ISBN 9789629371401. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ Roy, Denny (2004). Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 55, 56. ISBN 0-8014-8805-2.

- ^ a b c Laikwan, Pang (2024). One and All: The Logic of Chinese Sovereignty. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. doi:10.1515/9781503638822. ISBN 9781503638815.

- ^ "Taiwan Timeline – Retreat to Taiwan". BBC News. 2000. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ China: U.S. policy since 1945. Congressional Quarterly. 1980. ISBN 0-87187-188-2.

the city of Taipei became the temporary capital of the Republic of China

- ^ Introduction to Sovereignty: A Case Study of Taiwan (Report). Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education. 2004. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- ^ a b "The Chinese Revolution of 1911". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Fenby 2009, pp. 89–94

- ^ Fairbank; Goldman (1972). China. Crowell. p. 235. ISBN 0-690-07612-6.

- ^ Wang, Yi Chu. "Sun Yat-sen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "Sun Yat Sen elected president of new Republic of China". Shanghai: United Press International. 29 December 1911. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby, The Penguin History of Modern China (2013) p. 123.

- ^ Hsü 1970, pp. 472–474

- ^ "The abdication decree of Emperor Puyi (1912)". alphahistory.com. 4 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ McCord 1993, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Jonathan Fenby, "The silencing of Song." History Today (March 2013) 63#3 pp 5–7.

- ^ Fenby 2009, pp. 123–125

- ^ Fenby 2009, p. 131

- ^ Fenby 2009, pp. 136–138

- ^ Meyer, Kathryn; James H Wittebols; Terry Parssinen (2002). Webs of Smoke. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 54–56. ISBN 0-7425-2003-X. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Pak, Edwin; Wah Leung (2005). Essentials of Modern Chinese History. Research & Education Assoc. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-87891-458-6. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Guillermaz, Jacques (1972). A History of the Chinese Communist Party 1921–1949. Taylor & Francis. pp. 22–23. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Fenby 2009

- ^ 重編國語辭典修訂本 (in Chinese). Taiwan Ministry of Education. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2012. 民國十六年,國民政府宣言定為首都,今以臺北市為我國中央政府所在地。

- ^ a b Kucha, Glenn; Llewellyn, Jennifer (12 September 2019). "The Nanjing Decade". Alpha History. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ (Fung 2000, p. 30)

- ^ Chen, Lifu; Myers, Ramon Hawley (1994). Chang, Hsu-hsin; Myers, Ramon Hawley (eds.). The storm clouds clear over China: the memoir of Chʻen Li-fu, 1900–1993. Hoover. p. 102. ISBN 0-8179-9272-3.

After the 1930 mutiny ended, Chiang accepted the suggestion of Wang Ching-wei, Yen Hsi-shan, and Feng Yü-hsiang that a provisional constitution for the political tutelage period be drafted.

- ^ Eastman, Lloyd (2021). "Fascism in Kuomintang China: The Blue Shirts". The China Quarterly (49). Cambridge University Press: 1–31. JSTOR 652110. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Payne, Stanley (2021). A History of Fascism 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0299148744. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Jay (2009). The Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Harvard University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-674-03338-2.

- ^ Gregor, A. James (2019). A Place In The Sun: Marxism And Fascism In China's Long Revolution. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-98319-1.

- ^ Payne, Stanley (2021). A History of Fascism 1914–1945. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-299-14874-4. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Liu, Wennan (2013). "Redefining the Moral and Legal Roles of the State in Everyday Life - The New Life Movement in China in the Mid-1930s". Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review. 44 (5): 8–12. doi:10.1353/ach.2013.0022. S2CID 16269769 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan (2008). Chiang Kai Shek - China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780786739844.

- ^ Ferlanti, Federica (2010). "The New Life Movement in Jiangxi Province, 1934–1938" (PDF). Modern Asian Studies. 44 (5): 8–12. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0999028X. JSTOR 40926538. S2CID 146456085.

- ^ Hershatter, Gail (2019). Women and China's Revolutions. Critical issues in world and international history. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-442-21568-9.

- ^ Edwards, Louise; Milwertz, Cecilia Nathansen (2006). Hershatter, Gail (ed.). Women and Gender in Chinese Studies. Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-825-89304-0.

- ^ Jing, Zhiren (荆知仁). 中华民国立宪史 (in Chinese). 联经出版公司.

- ^ (Fung 2000, p. 5) "Nationalist disunity, political instability, civil strife, the communist challenge, the autocracy of Chiang Kai-shek, the ascendancy of the military, the escalating Japanese threat, and the "crisis of democracy" in Italy, Germany, Poland, and Spain, all contributed to a freezing of democracy by the Nationalist leadership."

- ^ Treaty between the United States and China for the Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China

- ^ Sino-British Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China

- ^ Urquhart, Brian. Looking for the Sheriff. New York Review of Books, 16 July 1998.

- ^ Brendan M. Howe (2016). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 9781317077404. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Jessup, John E. (1989). A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945–1985. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-24308-5.

- ^ Rummel, Rudolph J. (1994). Death by Government. Transactions Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56000-145-4.

- ^ Valentino, Benjamin A. (2005). Final solutions: mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century. Cornell Studies in Security Affairs. Cornell University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8014-7273-2.

- ^ "The Republic of China Yearbook 2008 / Chapter 4 Government". Government Information Office, Taiwan. 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Wilbur, Clarence Martin. The Nationalist Revolution in China, 1923–1928. Cambridge University Press, 1983, p. 190.

- ^ Li Shui. Chiang Kai-shek's chief bodyguard published a book revealing the 62-year history of "counterattacking the mainland" 13 November 2006. Archived 21 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Qin Xin. Taiwan army published new book uncovering secrets of Chiang Kai-shek: Plan to retake the mainland. 28 June 2006. China News Agency. China News Archived 14 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kaufman, Alison Adcock (November 2014). "In Pursuit of Equality and Respect: China's Diplomacy and the League of Nations". Modern China. 400 (6): 605–638. doi:10.1177/0097700413502616. JSTOR 24575645.

- ^ An, Kang (2020). To Play or Not to Play: A Historic Overview of the Olympic Movement in China From 1894 to 1984. The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ An, Kang (2020). To Play or Not to Play: A Historic Overview of the Olympic Movement in China From 1894 to 1984 (PDF) (Report). University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ "Republic of China at the Olympics". topendsports. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "1945: The San Francisco Conference". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Stephen Schlesinger, "FDR's five policemen: creating the United Nations." World Policy Journal 11.3 (1994): 88-93. online Archived 4 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wellens, Karel C., ed. (1990). Resolutions and Statements of the United Nations Security Council: (1946–1989); a Thematic Guide. Dordrecht: Brill. p. 251. ISBN 0-7923-0796-8. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Cook, Chris Cook. Stevenson, John. [2005] (2005). The Routledge Companion to World History Since 1914. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34584-7. p. 376.

- ^ "China's Representation in the United Nations", by Khurshid Hyder – Pakistan Horizon; Vol. 24, No. 4, The Great Powers and Asia (Fourth Quarter, 1971), pp. 75–79, Pakistan Institute of International Affairs

- ^ National Institute for Compilation and Translation of the Republic of China (Taiwan): Geography Textbook for Junior High School Volume 1 (1993 version): Lesson 10: pp. 47–49.

- ^ 1945年「外モンゴル独立公民投票」をめぐる中モ外交交渉 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ Xu, Yan (2019). The Soldier Image and State-Building in Modern China, 1924–1945. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 54, 57–59, 122. ISBN 9780813176765 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Setzekorn 2018, pp. 18–21.

- ^ Schillinger, Nicolas (2016). The Body and Military Masculinity in Late Qing and Early Republican China: The Art of Governing Soldiers. Lexington Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-1498531689.

- ^ McCord 1993, pp. 177–178.

- ^ McCord 1993, pp. 173–174.

- ^ McCord 1993, p. 186.

- ^ McCord 1993, pp. 207–208.

- ^ McCord 1993, pp. 247–250.

- ^ McCord 1993, p. 288.

- ^ Setzekorn 2018, pp. 27–28.

- ^ McCord 1993, p. 245.

- ^ a b Setzekorn 2018, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Setzekorn 2018, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Setzekorn 2018, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Setzekorn 2018, pp. 39–42.

- ^ a b Sherry 1996, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Setzekorn 2018, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Sherry 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Sherry 1996, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Sherry 1996, pp. 15–21.

- ^ Sherry 1996, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Setzekorn 2018, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Westad, Odd (2003). Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. Stanford University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-8047-4484-3.

last major GMD stronghold.

- ^ Cole, Bernard D. (2014). "The History of the Twenty-First-Century Chinese Navy". Naval War College Review. 67 (5): 6–7. Retrieved 1 February 2024 – via U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons.

- ^ Zhao, Xuduo (2023). Heretics in Revolutionary China: The Ideas and Identities of Two Cantonese Socialists, 1917–1928. Germany: Brill. pp. 71–74. ISBN 9789004547148.

- ^ a b Jordan 1976, p. 162.

- ^ Ministry of Defense of the Republic of China 2010, pp. 29–33.

- ^ a b c Elleman 2019, pp. 43–46.

- ^ a b c Chen 2024, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Chung 2003, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Chen 2024, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Elleman 2019, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Hao-Chang, Yu (November 1966). "Republic of China Marine Corps". Marine Corps Gazette. Marine Corps Association.

- ^ Braitsch, Fred G. (February 1953). "Marines of Free China". Leatherneck Magazine. Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Lance, John Alexander (2014). Icarus in China : Western Aviation and the Chinese Air Force, 1931–1941 (PDF) (Thesis). Western Carolina University.

- ^ Xu 1997, pp. 156–159.

- ^ Xu 1997, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Xu 1997, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Molesworth & Moseley 1990, pp. 3–6.

- ^ Xu 1997, p. 170.

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 613–614 [citation needed]

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 1059–1071

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 1353

- ^ a b Sun Jian, page 1089

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 615–616

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 1319

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 1237–1240

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 617–618